There is lot of confusion regarding the practice of dowry in Indian society.Though it’s now legally banned,it would not be out of place to understand its role in Indian society vis-à-vis the role of women in Indian society.Today we may be witnessing that there is loss in stature of Indian women but that was not the case in beginning of Indian civilization.True, dowry has become a potent weapon to harass the Indian women but that was not the case when this concept came in origin.

Have a loot at the excerpts from the paper published by Nidhi Gupta in “Journey of Legal Pluralism And Unofficial Law”.

The paper is titled : WOMEN’S HUMAN RIGHTS AND THE PRACTICE OF DOWRY IN INDIA:ADAPTING A GLOBAL DISCOURSE TO LOCAL DEMANDS.

3.2 Understanding dowry and the dowry problem There is no general agreement or certainty about the definition or origin of ‘dowry’. In strict terms, ‘dowry’ is what a bride’s parents give to the groom or to his family on demand either in cash or in kind. It can be looked as a settlement that is normally constituted of: (1) what is given to the bride, and often settled beforehand and announced openly or discreetly; (2) what is given to the bridegroom before and at marriage; and (3) what is presented to the in-laws of the girl. The settlement often includes the enormous expenditure incurred on travel and entertainment of the bridegroom’s party (Government of India 1974: 71). This definition can be extended to include also the giving of gifts or cash from the bride’s parents to her husband, his family or to herself after marriage, either towards fulfilment of the pre-nuptial settlement or on the basis of further expectations of the groom and his family. There is a common belief that dowry is an ancient Hindu practice, but there is no authoritative opinion available that tell us that ‘dowry’, as defined above can be traced to the ancient Hindus.

According to Altekar the dowry system was generally unknown in early societies and also with ancient Hindus. He specifically mentions that: “there are no references either in Smritis or in dramas to the dowry, i.e. to the pre-nuptial contract of payment made by bride’s father with the bridegroom or his guardian” (Altekar 1962: 69-72). However, there is general agreement that, while the Hindu belief system and practices cannot be held responsible for the custom of ‘dowry’ as such, there are some elements of the tradition that feed the roots of the dowry problem (Menski 1999a). Altekar says there was indeed a tradition of giving gifts to a son-in-law at the time of marriage but this was restricted to rich and royal families. He asserts that these gifts can hardly be called dowry for they were voluntarily made out of affection (Altekar 1962: 70). In respect of its elements he further clarifies: The dowry system27 is connected with the conception of marriage as a dana or gift.

A religious gift in kind is usually ( Altekar gives no clear indication about what he means by ‘dowry system’ here but it can be assumed that he implies it to mean voluntary transfer of property in any form to the bride, groom and groom’s family from the bride’s family at the time of marriage) accompanied by a gift in cash or gold. So the gift of the bride was also accompanied by a formal and small gift in cash or ornaments. (Altekar 1962: 71. See also Government of India 1974: 72-73) _____________________

He traces initiation of this custom to medieval times and to Rajputana but always wrapped in love and affection, with no element of coercion. Another commonly accepted explanation, which traces elements of dowry to the ancient Hindu belief structure, views it as a kind of pre-mortem inheritance of the daughter, who has to leave her natal family to join another (Government of India 1974: 71). Many authors have put forward the claim that giving of cash or gifts, mainly moveable property, to the daughter at the time of marriage was a kind of compensation for the absence of inheritance rights in their father’s property for daughters. Dowry, thus, stresses the notion of female property and a female right to property, it being viewed as an important ingredient of streedhan. It has been claimed that the custom had its origin in agricultural societies where the family’s survival was dependent on its holding land. Since women joined the husband’s family after marriage, they were not given a formal share in the land, mainly to avoid the fragmentation of land Das 1962: 43-99). Ram Mohan Das states: We find that Manu has made a very practical approach to the problem. He recommends one-fourth share and thereby provides for the marriage expenses of the daughter.

At the same time by allotting one-fourth share he clearly indicates that the brothers should not unnecessarily waste money over the marriage of their sisters. (Das 1962: 80-81) He explains that sons were given a specific one-fourth share of the ancestral property to meet the marriage expenses of their sisters. This share on the one hand was meant to ensure financial security for her and on the other to put a limit on unnecessary marriage expenses. Given the nature of the evidence that is available for knowing and understanding ancient Hindu practices, it is true that there is no certainty whether dowry can really be connected to streedhan or not.

There are conflicting views about this, and some authors have argued that women were merely vehicles for the transfer of property from one family to another, and had no right over property transferred in the name of dowry (Kishwar 1986: 2-13; Stone and James 1997). But for our purposes, it is important to note that this explanation also lays stress on the discretion that the bride’s family enjoyed in respect of the worth of the dowry and on the element of natural love and affection. As is evident none of the available explanations which try to trace theorigin of ‘dowry’ correspond to the understanding of ‘dowry’ in the modern sense. These opinions underscore the view that, except for some of its elements, and even in respect of those with many variations, it is wrong to consider ‘dowry’ asan ancient Hindu practice. On this basis it is not wrong to assert that ‘dowry’ – a custom that involves pre-nuptial financial settlement between bride and groom’s family; transfer of property as a consideration for marriage; continuing extortion from the bride’s family even after marriage; torture or killings of young brides either for breach of marriage settlements or with an intention to benefit further from them – has nothing to do with the ancient Hindu belief system. Menski rightly points out: Killing a woman, and certainly killing a bride at the point of entry to that phase of life where she was supposed to be most productive, would become viewed as the most heinous of the violations of the eternal Order (rita) that the Hindu worldview revolves around (Menski 1999a: 6). The ‘dowry’, a custom that is strongly condemned today, is a modern phenomenon – ‘a modern custom’. Consequently both the approaches, that is, one that puts the blame squarely on the tradition for perpetuating oppression of women in name of customary practices, and another that defends the practice on the basis of ancient traditional origin, are misplaced.

Yet, the complexity of the whole issue arises from the fact that, though ‘dowry’ as such cannot be traced to Hindu tradition, certain elements of the Hindu belief system and practices feed it. Given this connection with the ancient Hindu belief structure it is necessary to redefine what exactly can be considered the dowry problem and how to deal with it on the basis of these elements.

In spite of great variations in the understanding of dowry, one can say that the predominant understandings especially the one that is sensitive towards cultural diversity, suggest that only ‘dowry’, that is, those financial and material transactions around marriage that have elements of demand in them, should be considered problematic. There is no clarity about how to view other kinds of financial and material transactions associated with marriage in India, which cannot be considered per se objectionable but which are directly and indirectly responsible for ‘dowry’ and the dowry problem.

http://www.jlp.bham.ac.uk/volumes/48/gupta-art.pdf

*****************************************************************

Now let’s have a look at the situation of women in ancient Indian society.

”Women enjoyed far greater freedom in the Vedic period than in later India. She had more to say in the choice of her mate than the forms of marriage might suggest. She appeared freely at feasts and dances, and joined with men in religious sacrifice. She could study, and like Gargi, engage in philosophical disputation. If she was left a widow there was no restrictions upon her remarriage.”

Source:

Will Durant – Story of Civilization: Our Oriental Heritage

_____________________________

“Among the many societies that can be found in the world, we have seen that some of the most venerating regard for women has been found in Vedic culture. The Vedic tradition has held a high regard for the qualities of women, and has retained the greatest respect within its tradition “

Source -Stephen Knapp- Women in Vedic Culture.

_________________________

”Women were held in higher respect in India than in other ancient countries, and the Epics and old literature of India assign a higher position to them than the epics and literature of ancient Greece. Hindu women enjoyed some rights of property from the Vedic Age, took a share in social and religious rites, and were sometimes distinguished by their learning. The absolute seclusion of women in India was unknown in ancient times.”

Source:

R. C. Dutt – The Civilization of

India

____________________________

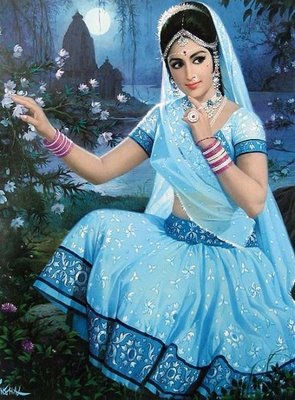

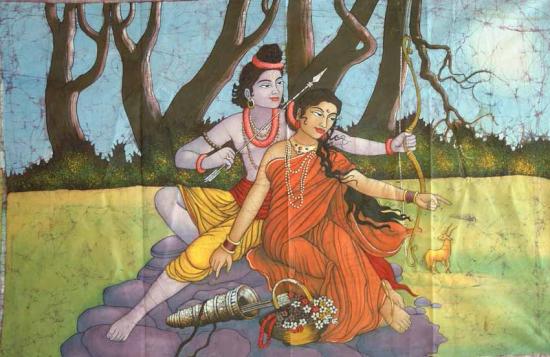

In ancient times Aryans were the main inhabitant of India. These people were mainly Brahmins and they used to give the status of goddess to the women. At that time women enjoyed no less than status of Lakshmi (goddess of wealth) in the households. A famous Sanskrit shloka (form of Hindu verse) signifies the status of women in that era, ”Yatra naryastu pujyante, ramante tatra devta” meaning, “The place where women are worshipped, god themselves inhabit that place”. The women of ancient times had immense power this is evident from a South Indian legend that once a king accidentally killed the husband of a women and she had such powers that she burnt the whole kingdom to ashes. Women in that time had place even superior to men. They had representation in each arena from assemblies to religious rituals. In fact no religious ritual of Hindu Brahmins was supposed to be complete without the presence of the women. An incident of Ramayana is a proof of this as when Lord Rama was performing Ashvamedha yajna his wife Sita was not with him and he had to use the gold idol of his wife to compensate for her absence. Ancient Indian women had say in each and every aspect related to their lives. They had the right to choose their own life partners.

The process of choosingthe life partner of own choice was known as Swayamvar in which grooms assembled at the house of bride and she used to choose the one whom she liked. Maharishi Ved Vyas’ Mahabharata and Mahrishi Valmiki’s Ramayana bear testimonial to this. In Ma-habharata, Draupadi’s father arranged for her Swanyamvar and Arjuna (a Pandavamarry her.

Even the model women of Tretayuga, (second out of four ages of Hindu mythology) Sita also had Swanyamva in which kings of different states participated and Lord Rama won her over by breaking the Shiv Dhanusha (Hindu God Shiva’s bow).Not only just princely women but the common women were also given the same rights. Women were so important that many of the major battles were fought for them. The fiercest battle of ancient India Mahabharata was fought for the honor of Draupadi (wife of Pandavas, ruler of Indraprastha). The Kauravas (ruler of

Hastinapur) insulted her in the court and this led to the enmity between cousins and resulted in the most devastating battle of ancient India.

Another example of women power is evident from the cause of death ofmost learned man of his time Ravana. He was the best scholar of his time and was the master of all the four Vedas of Hindu religion and had immense powers. Even gods were not able to defeat and kill him but a woman was able to bring his doom. Ravana

captured Sita and tried to mart her forcibly which led to his destruction.

Women were not just confined to domestic arena but they were also part of religious teachings. In ancient India woman like Gayatri, Maitreyi, Anusuya were re-nowned seers of their time this shows that women had the right to religious

teachings. They were not prohibited even from learning. They could learn whatever they wanted.

Vedas, the most adored Hindu scripture, give respectable position to women. Rig Veda allows share in property to the daughter who resides for eve r with her parents (2-17-6). It gives right to girls to choose their life partners or husband (10-27-12). A hymn of Atharva Veda says: May women be united with handsome husbands. They should never be widows and never be in tears. May they be very prosperous and rich! May theywear pretty garments and beautiful ornaments and may they wish to take rebirth in human yoni (form) to maintain perpetuity of humanity.. A husband is supposed to request and praise her wife and get her voluntary consent if he wishes to have sexual union with her.

From ”The History Of Indian Women: Hinduism At Crossroads With Gender” by Babita And Sanjay Tewari

************************************

Position of Women (Page 227), (Manu Smriti, 3.55-5; 9.3-7, 11, 26) ”

Women must be honored and adorned by their fathers, brothers, husbands,

and brothers-in-law who desire great good fortune. Where women, verily,

are honored, there the gods rejoice; where however, they are not

honored, there all sacred rites prove fruitless. Where the female

relations live in grief – that family soon perishes completely;

****************************************