“Tlatelolco is symbolic of everything that is negative about Mexican authoritarianism — impunity, violence, silence, control of the media.”

For Mexico, 1968 was a special year, one in which it would host the Olympics during October 5-27 to demonstrate to the world how modernized and civilized it was. The Mexican economy had been booming for years and was to be displayed so the world would know that the nation had arrived.

President Díaz Ordaz and other government officials believed, no doubt, that hosting the Olympics was the most important act of the year, if not of decades, and that nothing could be allowed to interfere with this great enterprise. Believing this, they assumed that all other Mexicans were equally concerned with the Olympics; they did not recognize the causes of nor understand the rationale behind the youth cult flowering in the 1960s and the emergence of the iconoclastic New Left.

In July 1968, the mayor of Mexico City sent the riot squad to stop a fight during a soccer game between a technical school and a preparatory school, the citizens of the Federal District began to take a more critical view of government. The granaderos broke up the fight, followed the students into the school building, and beat them. Following this event, a student demonstration was held to protest the police brutality, which turned into a violent battle between police and students that lasted for days. Students burned buses, police beat students, and students were arrested and jailed.

On August 1, 1968, President Gustavo Diaz Ordaz delivered the informe, the annual State of the Union message from Guadalajara, in which he promised his government would engage in a dialogue with the students. When no progress occurred, student leaders led a mass march on August 27th to the Zócalo, the central plaza bordered by the National Palace, the National Cathedral, and the city hall. Not only did they protest, but decided to leave more than 5,000 people there to “hold” the plaza, the heart of the nation, hostage; the act was seen as a direct threat to the authority of the national government. The movement had gone too far. Soldiers, police, and firemen retook the Zócalo in the early hours of August 28th, using extreme, indiscriminate force.

Pressure to end the student movement before the Olympics increased. Foreign reporters were reporting the events; Mexico responded by condemning the students via media as Communist, paid by foreign governments, an embarrassment and threat to Mexico.

On September 18th, the army invaded the headquarters of the student movement, UNAM campus. The invasion of sparked a wave of violence, but the weakened movement would not surrender. Soldiers in jeeps, armored cars, and tanks guarded the main streets of the city. On September 28, the leaders and government agreed on a joint dialogue; the leaders publically insisted the removal of the army from the UNAM campus before the dialogue and promised not to interfere with the upcoming Olympic Games. On September 30, the army was removed and negotiations for peace began, however the movement still called for another mass meeting in Tlatelolco on October 2nd to protest the continued occupation of the city by the army. The protest was be followed by a peaceful, silent march.

In the late afternoon of October 2, thousands of protesting students and curious community families assembled in Tlatelolco’s Three Cultures Plaza. As the afternoon turned to evening, a helicopter appeared in the sky over Tlatelolco and began to drop flares. Unbeknown to the students and innocent bystanders, tanks and soldiors waited outside the entrances to the plaza. The tanks and the soldiers were ordinary business for the government, the flare throwing helicopter was not.

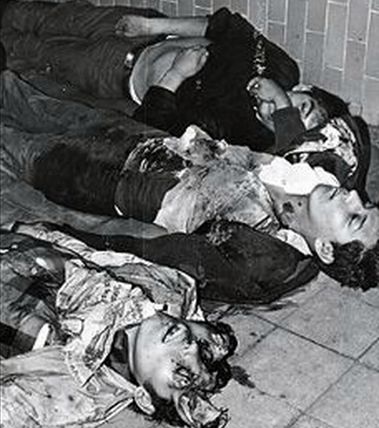

The machine guns opened fire first, soldiers and tanks came rushing in, closing off the exits, turning the crowd into a confused, terrified mob. For sixty two minutes, parents and their children screamed, gunfire came from every direction; then the massacre ended. No one was permitted in or out of the plaza, no ambulances for the wounded, thousands of innocent lay in streets that wept blood.

A heavier rain of bullets than any of the ones before began then, and went on and on. This was genocide, in the most absolute, the most tragic meaning of that word. Sixty-two minutes of round after round of gunfire, until the solders’ weapons were so red-hot they could not longer hold them.

Leonardo Femat

Now that I’d managed to get to Julio and we were together again, I could raise my head and look around. The very first thing I noticed was all the people lying on the ground; the entire Plaza was covered with the bodies of the living and the dead, all lying side by side. The second thing I noticed was that my kid brother had been riddled with bullets.

Diana Salmeron de Contreras

The special presidential guards of the Olympia Brigade and the Army tore the clothes off the people they thought were student leaders as means to identify them before gathering them and taking them away. Journalists in the crowd photographed the nearly naked students, the shreds of the clothing hanging around their battered, bloodied bodies. Five hours after the helicopters had dropped the flares, the first ambulances were allowed into the plaza.

Although the estimated death toll was between 300 and 500, the police released an official statement saying only twenty-six were killed, thus only twenty six autopsies were performed. The leaders of the protest were tortured, beaten, burned, shocked, and humiliated for days. Of course, after exhaustive investigation it was proved, they had no secrets nor money from foreign governments.

In spite of official Olympic propaganda promoting Mexico as an emerging democracy which sought social justice, the 1968 student movement revealed the system for what it was: authoritarian, sometimes brutal, and primarily interested in making the rich richer. In spite of a federalist, democratic constitution, the nation was ruled centrally from Mexico City, social services were dispensed according to political imperatives not need and income disparities were increasing.

Fourty years to the day, and not one sentence is written in school textbooks about the bloodiest massacre of Modern Mexico. All that took place at Tlatelolco in 1968 was and remains an official secret of public knowledge.